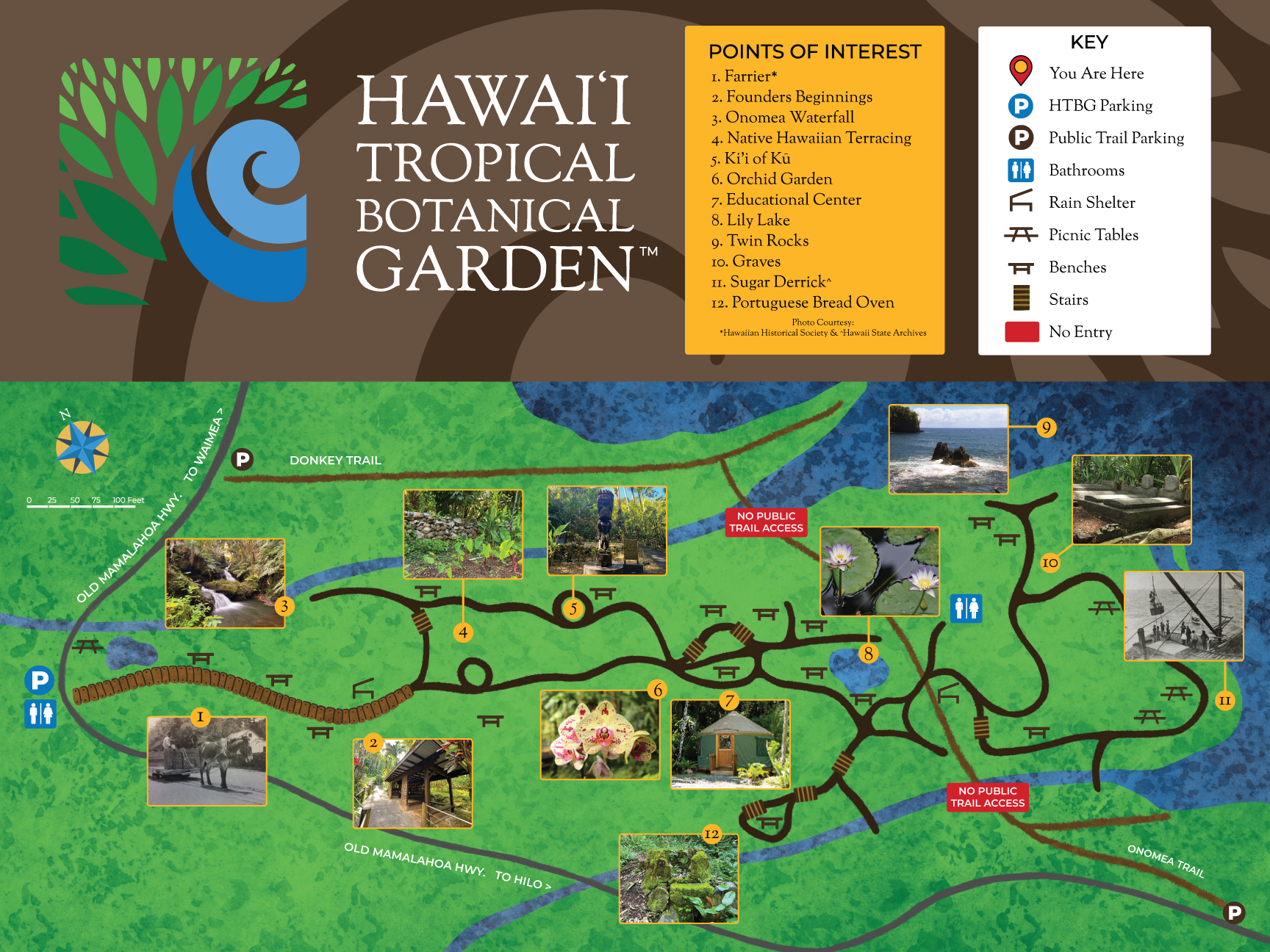

HTBG INTERACTIVE MAP

GARDEN MAP

The garden trails meander through our unique habitat with plenty of spots to stop and admire your surroundings

Or click below to discover more about what you'll see

Click on the images in the Map to learn more.

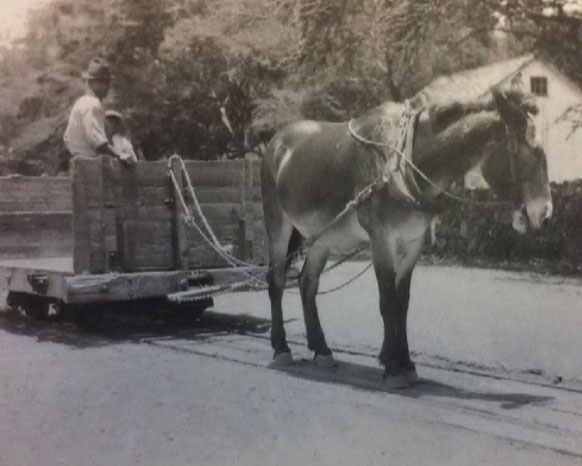

I: Farrier

Across from the Boardwalk, you will see a stone-walled platform. A Chinese shop stood there serving as a farrier. Farriers are specialists in hoof care for horses and donkeys. The word farrier derives from the Latin ‘Ferrarius’, meaning ‘iron’ or ‘blacksmith’. The farriers would make shoes for the donkeys that carried the bags of sugar down to the shore. Many donkey shoes have been recovered from this site.

Chinese laborers were the first immigrant group to arrive in Hawaii for work on the plantations. They began arriving in Hawaii a half-century before other ethnic groups. They were the first to fulfill their labor contracts and leave plantations. About a third returned to China. Many decided to stay and start families here to provide their children better opportunities. Many Chinese laborers went into different businesses, collectively creating one of Hawaii’s first middle classes.

II: Founders Beginnings

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS

The Founder, Dan Lutkenhouse Sr. discovered the Onomea Valley while on a vacation to the Big Island of Hawai’i in 1977. Lutkenhouse was in the process of selling his 40-year-old trucking business in California and retiring. He and his wife agreed that this is where they would like to spend the rest of their lives. They purchased the 17-acre parcel for its seclusion and beauty and once Dan began exploring the land, he decided to establish a botanical garden in order to preserve the valley and its beauty forever.

Onomea Valley was once an overgrown and virtually impenetrable jungle, choked with invasive species, weed and thorn thickets. Every day, seven days a week, until the Garden opened in 1984, Dan, his assistant Terry Takiue, worked with cane knives, sickles, picks, shovels and a chainsaw to clear paths through the jungle.

Founder’s Beginnings

His wife, Pauline, would pack Dan a brown bag lunch and he would disappear into the jungle, returning at night dirty and tired. All the work was done by hand to avoid disturbing the natural environment or destroying valuable plants and tree roots. Trails were hewn from hard lava rock with picks and shovels. To keep the soil from compacting and the natural beauty from being destroyed, no tractors were used, excess rock was removed, and gravel brought in by wheelbarrow. Without formal botanical training, but with a love of nature and the Onomea Valley, Lutkenhouse created a living tapestry of plants. Lutkenhouse followed the contours of the land in designing the Garden trails, which curve and wind their way throughout the jungle. Gradually, secret landscapes revealed themselves. It took years of carefully clearing the jungle before he discovered one of the crown jewels of the Garden – a three-tiered waterfall said to be the most beautiful in all Hawaii which can be viewed at Onomea Falls in the Garden.

THE NEXT FORTY YEARS

Over the course of the next 17 years, Dan lovingly cultivated, collected and planted over 2,500 tropical and subtropical plants, both native and species from around the globe. Over 100 of these species were personally procured on plant collecting trips to countries as far as Madagascar. Dan and Pauline cultivated relationships with local horticulturists and brought back plants and trees from other tropical environments. Some of these plants are now extinct in the wild and the Garden remains a seed bank for these species to live on for future generations. After the passing of Dan Lutkenhouse Sr. in 2007 and Pauline Lutkenhouse in 2017, Dan’s children Dan Lutkenhouse Jr. and daughter Debi Lutkenhouse-Frost took over operation of the Garden under the guidance of the Board of Directors. Their vision is to use the power of the existing Garden to create a larger hub for sustainability education and climate change.

III: Onomea Waterfall

Onomea Waterfalls is a three-tier waterfall with Onomea Stream originating from Kawainui (The Big Water) Stream. Onomea stream further connects downstream with Onomea Bay. The waterfall is nestled within thick vegetation of palm trees and ferns, and mosses are growing on the surrounding rocks and trees. It is a serene spot that emits a rejuvenating energy.

IV: Native Hawaiian Terracing

Three ahupua’a come together on this peninsula: Onomea, Kahali’i and Alakahi. The first settlers of the bay were the Native Hawaiians living in a fishing village called Kahali’i. The village thrived until the early 1900s. Kahali’i means “small cut.” Luika Pererra one of the last residents of the village explained: “Kahali’i has a flat rock that goes ¾ of the way around the bay and it is under water. If a large ship or canoe would come in, it would puka (hole) their boat. So, to come in either direction would mean your death. But if you came in here at Kahali’i, you would live. The name implies the smallest opening that you can come through safely.” Today, traces of the Kahali’i fishing village are prominent in this area.

After a 100 year old Banyan Tree fell and destroyed the Heliconia Trail, it revealed old terraces. These terraces were used to plant taros, bananas and other fruits and vegetables needed to sustain the village. With our replanting and reforestation efforts, we’ve been able to add more native and canoe plants in Heliconia Trail.

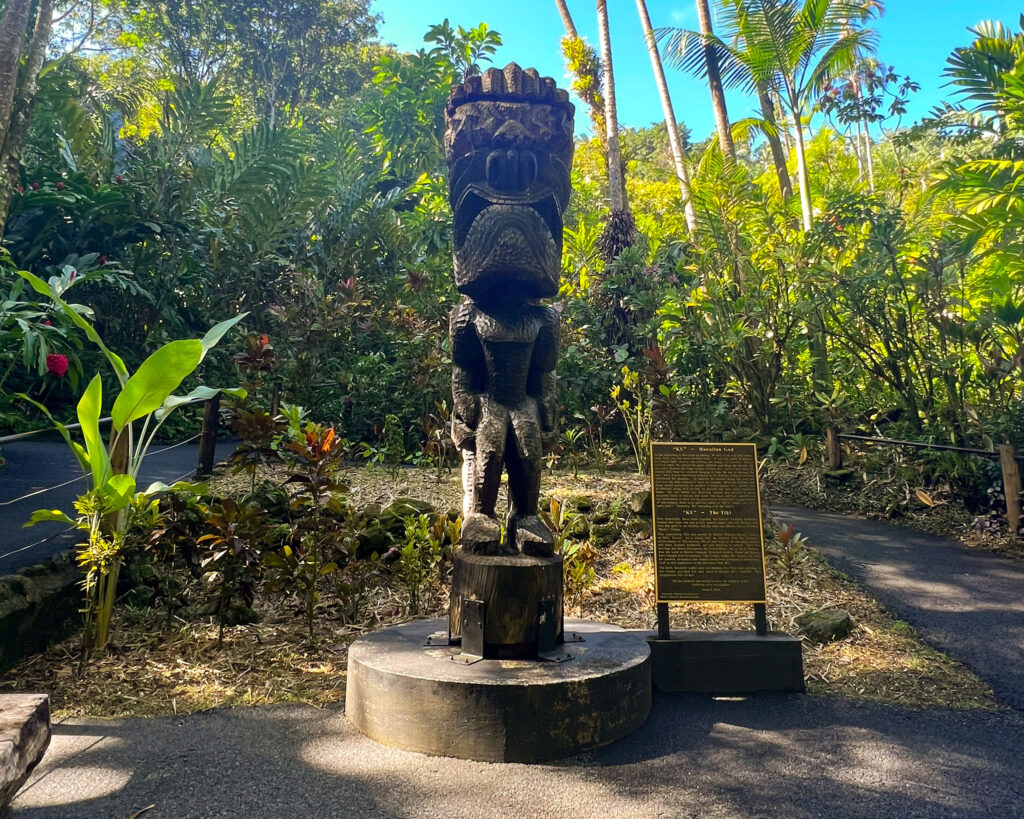

V: Kiʻi of Kū

Kū, the God of War is one of the four great gods of Hawaii along with Kanaloa, Kāne, and Lono. The outstanding Ki’i of Ku was carved by William (Rocky) Vargas of Hilo, Hawaii using an 80-year-old Monkeypod tree that once stood in the Garden. As a young boy, his interest in wood carving was inspired from his brotherʻs achievements in carving tikis. He later studied woodwork, art and drafting. Now his carvings are shown throughout the United States, internationally, and famously, Kiʻi of Kū at HTBG.

VI: Orchid Garden

The Island of Hawaii is known as the Orchid Island

The Orchid Isle is named for the commercial orchid industry which took hold In Hawall in the 1940's. The commercial Orchid trade originated mainly from Tropical American and Indian species. For more than 150 years, orchid growers have created over 150,000 hybrids by cross pollinating different orchid species or hybrids. Our Garden's collection contains all the main tropical Genera: Vanda, Cattleya, Phalaenopsis, and Oncidium as well as many more. Our collection also contains nonnative orchids which have “naturalized” themselves in the wild throughout the island. These orchids are Spathoglottis, Phalus, Epidendrum and Arundina. There are only three orchid species truly native to Hawaii, which are rare and found only in high elevations.

Orchids comprise one of the largest families of flowering plants and can be found growing in nearly every region of the world, even the arctic. The tropics contain 1,000 Genera and 15,000 species of orchids. Most of the tropical species are epiphytes and in their natural environment grow on trees, sometimes very high up to reach the light and air. They send down long aerial roots that serve to anchor to the host tree. Nourishment is absorbed mainly through the leaves in the form of minute particles of organic matter. Orchids of temperate and arctic climates are primarily terrestrial and draw their nourishment directly from the ground. Some orchids flower on and off throughout the year while others will flower but once. The spice vanilla is the seed pod resulting from the pollinated flower of the tropical orchid vanilla planifolia. Please enjoy these beautiful orchids and don't miss those attached to the trees in our Garden!

VII: Coming Soon: Educational Center

Coming soon to HTBG: Educational Center featuring history of Onomea Bay.

VIII: Lily Lake

Located at the center of the Garden, Lily Lake looks as though nature placed it there. Our founder, Dan Lutkenhouse dug the lake by hand and the bottom was lined with hand poured concrete three inches thick to contain the water. Over 100 species of tropical plants can be seen in Lily Lake. Among them are Queen Victoria water lilies from Victoria River, Africa; Wi apple tree, Travelerʻs Palms, and a variety of betel nut palms. The lake is home to a school of large koi fish, some as long as 30 inches. Skirting the lake, the trail passes multi colored crotons, ti plants and canopies of giant Monkeypod trees.

IX: Twin Rocks

The legend of Twin Rocks states that the two rocks are a young man and a woman. The locals know them as the "lovers of Kahali'i." According to the legend, a chief of the village saw many canoes heading in the direction of the village. He called the elders of the village together to determine what to do, because he thought they were being attacked. Their plan was to build a reef that would block enemy ships from landing on their beaches. Because they didn't have a way to get the job done quickly enough, the asked two young lovers to be their protectors and guides. The lovers willingly gave their lives to protect the village, which became silent and dark to wait out the night.

In the morning, the villagers went out to find that the lovers were gone and two rocks had taken their place. The rocks now stand as sentinels to guard the village and the beaches from enemies.

X: Graves

Long ago, Onomea Bay was a fishing village, became a rough-water seaport in the 1800's, and later was inhabited by Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese and Filipinos who came here to work in the sugar cane fields and to help build the Onomea Sugar Mill. In the early 1900's, Onomea was deserted and vegetation grew so densely that few signs of habitation could be seen.

When our Founder and his tireless helpers were first clearing this area, they discovered this olden and dignified gravesite. We have never been able to authenticate the origin, although some old-timers believe the gravesite may have belonged to a caretaker's family, since a cement- made gravesite would not have pre-dated the 1900's. Our commitment is to forever preserve this resting place with the utmost care and respect.

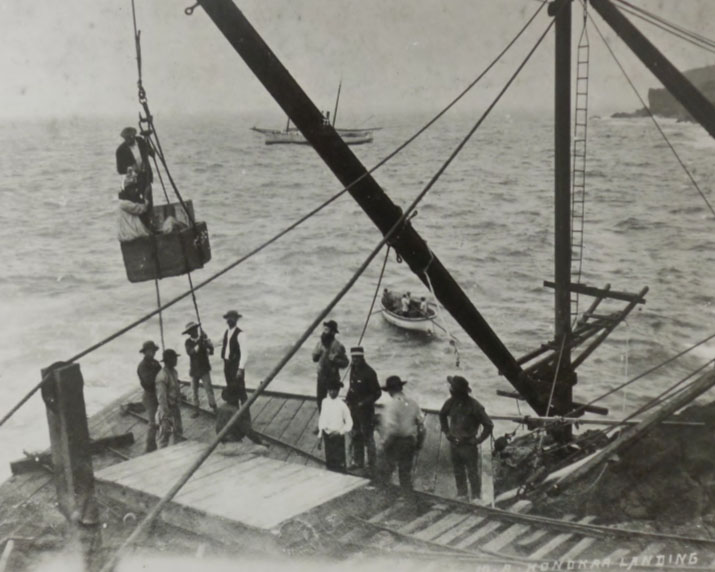

XI: Sugar Derrick

The Hamakua Coast is characterized by 50 mile bluffs from 100 to 400 ft above sea level. All plantations sat atop the bluff. Various means were designed to move loads between them and offshore boats. The majority of these were “wire landings,” with loads transported on wires strung from the top of the bluff to carefully moored ships. There was such a rig here in Onomea. Ships would anchor at Hilo Bay at night and depart in the early morning hours between 2 and 4 a.m., to arrive at the landings by daylight. There were four mooring buoys with heavy anchors to hold the ships. The water was deep but close to shore along the coast. Derrick landings were considered dangerous in rough weather. The sea and wind made it rough at these landings. The north wind was dangerous as the crew depended on the stern mooring lines to hold them in place. There were derrick landings, one of which was located here. Bags of sugar were brought down by donkeys and were loaded by a wooden derrick onto small boats called tenders. These tenders then transported bags out to a moored ship. Such landings were considered more dangerous in rough weather than wire landings. If you look closely, you will see in the rocks the bases of posts that were cut off. This may have held a cable to secure tenders. The larger ship achors in deeper water further offshore waiting to be loaded with sugar.

XII: Portuguese Bread Oven

Portuguese families first arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in 1878. Most immigrants hailed from the Portuguese volcanic islands of Azores and Madeira. The oven (forno) is made from lava rocks. These wood burning ovens were low domes of stone stuccoed over with clay or cement. Some fornos belonged to a single family, while larger ones were communal. Fire built inside heats the stones, it is then swept out. Bread dough, in pans, is placed inside, and the door is sealed. The heat from the stones cooks the bread. The Portuguese sweet bread is usually eaten during religious holidays such as Christmas, Easter and Lent. Onomea Bay was also settled by immigrants during the sugar plantations period. The remains of this forno indicates that a single Portuguese family was resident in this valley.